Introduction

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a minimally invasive procedure for the upper gastrointestinal tract using flexible endoscope. There may be several complications including bleeding, infection, and vomiting which could be resolved spontaneously. However, in rare cases, there may be perforation in the cervical esophagus or hypopharynx, which can be fatal and require surgical repair [1,2]. Symptoms and signs that can occur due to perforation include subcutaneous emphysema, pain, dysphagia, and even sepsis [3]. If perforation in the esophagus or hypopharynx does not heal spontaneously, there is a possibility of deep neck infection and mediastinitis [4]. Where conservative management and surgical approaches are used for the treatment of iatrogenic perforation, there has been no consensus for the appropriate treatment.

We would like to introduce a case of surgical repair of persistent hypopharyngeal perforation after EGD that did not improve with prolonged conservative treatment.

Through this case, we review of the literature for the diagnosis and surgical procedure for hypopharyngeal perforation after EGD.

Case

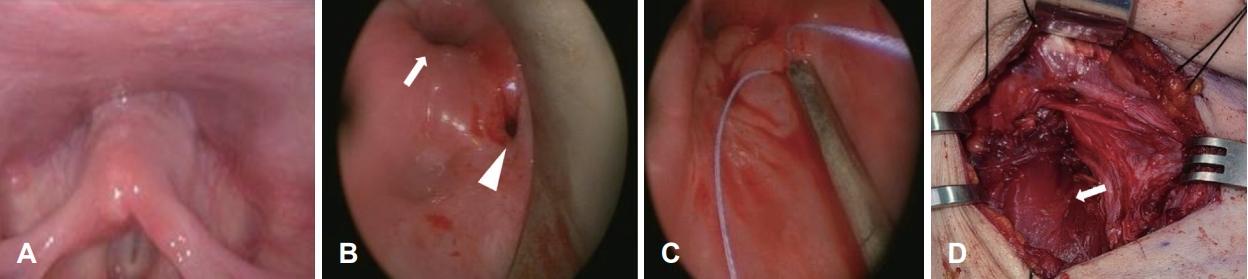

A 55-year-old female received EGD for dyspepsia. During EGD under sedation, there was excessive resistance felt in the endoscope as it passed through the upper esophageal sphincter area. As a result, the endoscope could not pass through the upper esophageal sphincter and the procedure failed. She was admitted to the hospital with persistent neck pain. Laryngoscopic findings revealed no evidence of perforation or inflammation (Fig. 1A).

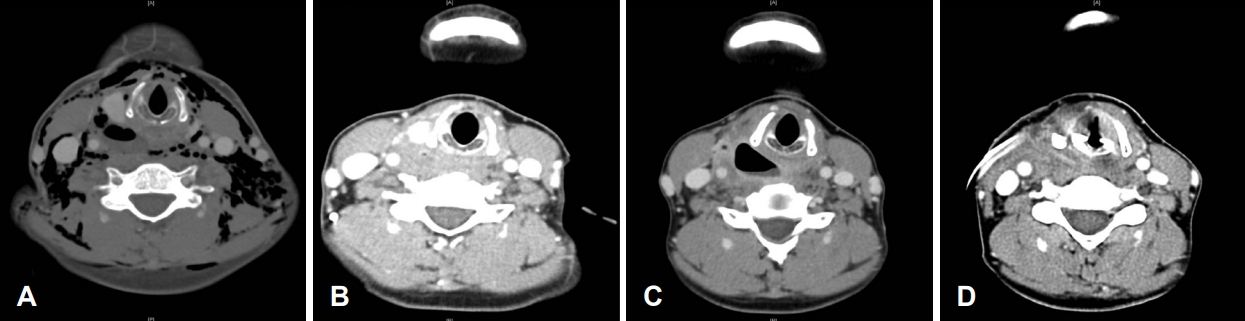

A contrast enhanced CT scan of the neck and thorax revealed extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 2A), with a suspicious air bubble observed in the area around the right side of the hypopharynx. A physical examination revealed crepitus in the neck and chest area, along with right-sided neck pain, but no subjective respiratory distress.

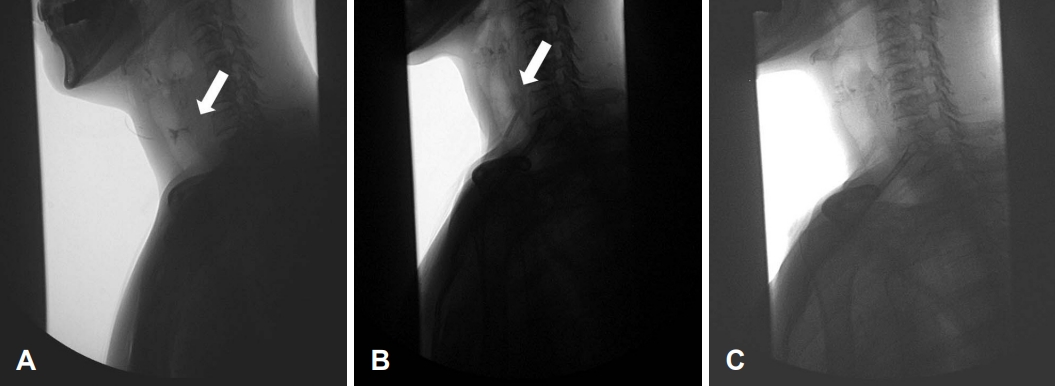

On esophagography, contrast leakage was found (Fig. 3A). Since the perforation of the hypopharynx was made iatrogenic and the patient preferred conservative management rather than external surgical approach, she was first treated with conservative treatment. Empirical antibiotics (ampicillin/sulbactam) combined with prohibition of oral intake was prescribed. One month after the event, the subcutaneous emphysema spontaneously resolved and minimal pooling of contrast in cervical esophagus without definite leakage was observed on esophagography (Fig. 3B). Two months after perforation, a small air pocket was seen but markedly decreased on neck CT (Fig. 2B). At that time, she was discharged in a condition where subcutaneous emphysema did not worsen, and oral intake was possible.

One week after discharge, she experienced worsening neck discomfort, and CT scan revealed an increase in the size of the previously observed air pocket (Fig. 2C).

An endoscopic evaluation under general anesthesia was done to find and treat the perforation. We found the perforation in the right postcricoid area, which was repaired with mucosal trimming and suture through transoral route (Fig. 1B and C).

Subsequently, a cervical incision was made to explore the site of the perforation bed. The area where the perforation had occurred was filled with granulation tissue. We removed the granulation tissue and cleansed the area with extensive irrigation. The hypopharynx perforation site was then reinforced using a sternocleidomastoid muscle rotational flap (Fig, 1D). The sternocleidomastoid muscle was resected in the inferior portion and was rotated superiorly based. The resected part of sternocleidomastoid muscle was anchored to the postcricoid area.

Discussion

EGD is a widely used procedure for diagnosis and treatment of upper gastrointestinal tract disorders, and it is usually performed safely without major complications. However, complications such as cardiac and pulmonary side effects, sedative-related side effects, infectious complications, perforation, and bleeding have been reported rarely [5]. Among these complications, perforation is very rare but can be life-threatening. The incidence of perforation associated with EGD is reported to be approximately 0.008% to 0.11%. The mortality rate when perforation occurs is reported to be 4.2% to 17%, mostly due to esophageal perforation [6]. Though some cases of hypopharynx perforation after EGD were reported, there was no case of pyriform sinus perforation. The only reported case of hypopharyngeal perforation was in a series of 10000 transesophageal echocardiography, and the management of which was not described [7].

The mucosal membrane in the hypopharynx is very thin and fragile, which is separated from the carotid sheath by a small muscle layer of the neck [8]. This is why hypopharyngeal perforation might be easily made but if not treated well, be fatal.

Since the perforation of the hypopharynx is often missed during the procedure, it might be found in a delayed manner. Symptoms such as sore throat, dysphagia, or subcutaneous emphysema may develop, and be a sign of hypopharyngeal perforation [9].

If perforation of the hypopharynx occurs during EGD, conservative treatment and surgical treatment are possible treatment options. Conservative treatment includes broad-spectrum antibiotics and prohibition of oral intake. If the patientвҖҷs symptoms improve with conservative treatment, surgery can be avoided, and associated morbidity can also be avoided. However, if the patient does not improve from conservative management, surgical treatment is inevitable. This can attempt surgical drainage, primary closure of the perforation site, and reinforcement of the perforation site with a muscle flap [1,10]. However, the ideal surgical treatment method is not determined. To determine this, various factors should be considered, and all patient-related factors should be checked when deciding on treatment. The factors to be considered include the size, location, cause, time to diagnosis, imaging findings, and general condition of the perforation.

Some retrospective studies have analyzed the treatment results of esophageal perforation related to EGD. Zenga, et al. [1] preferred surgical treatment, stating that if a patient had eaten before diagnosis or if more than 24 hours had elapsed between injury and diagnosis, signs of systemic toxicity, surgical treatment should be considered because conservative treatment is likely to fail. They reported that conservative management could be attempted for patients without these risk factors. On the other hand, Abbas, et al. [11] surveyed 119 patients with esophageal perforation and reported that if the diagnosis was made within 24 hours after the injury, the prognosis was good with conservative treatment. They reported that surgical treatment should be considered if the diagnosis was delayed or if there were signs of severe mediastinitis or empyema.

In our case, the diagnosis was made, and symptoms and emphysema were improved with conservative treatment.

In this case, the patient showed a pattern of improvement with long-term conservative treatment. However, due to her persistent neck discomfort, she eventually underwent surgery. There was a lack of surrounding muscle tissue and a dead space due to prolonged inflammation and granulation around hypopharynx perforation. Thus, we performed primary closure of perforated mucosa after mucosal trimming, and reinforcement of the area with sternocleidomastoid muscle rotational flap.