Introduction

Recently, nasopharyngeal swabbing has gained public attention due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus [1]. A broad array of sampling techniques have been introduced to confirm the presence of SARS-CoV-2, such as testing bronchoalveolar lavage fluids, sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, and saliva [1]. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended nasopharyngeal swabs as a cost-effective and sensitive test [2]. These swabs enable direct sampling of the posterior nasopharyngeal wall, which usually contains a large amount of the SARS-CoV-2 virus [1,3]. However, as more healthcare workers from diverse healthcare roles collect nasopharyngeal swabs, the question has been raised about the correctness and safety of performing these swabs. Although the prevalence is very rare, complications after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabbing have been reported; for example, one patient had uncontrollable nasal bleeding after a nasopharyngeal swab, which was managed by surgical intervention [4], and another patient, with a pre-existing skull base defect, had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, which also required surgical intervention [5]. Recently, we encountered a patient with pain in the left hemifacial area, which developed shortly after receiving a COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab and continued for over four months. After neurologic and rhinologic evaluations, a pre-existing mucosal contact point was found to be mechanically damaged by the nasopharyngeal swab and was suggested to be the painвҖҷs origin.

Case

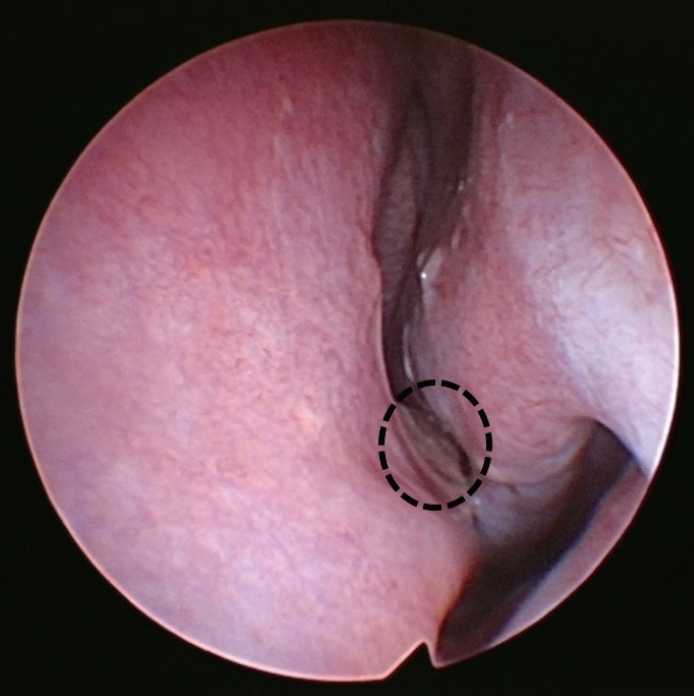

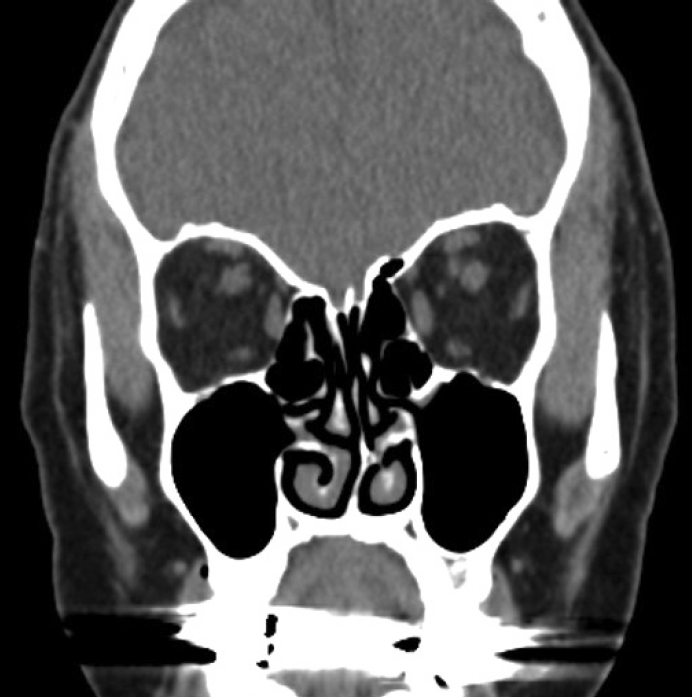

A female in their 70s presented to our clinic with left hemifacial pain, which had developed four months prior. The patient had previously received a COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab through her left nasal cavity, and the symptoms developed immediately after the swab. The patient had no other symptoms including epistaxis after the swab except the facial pain. The patientвҖҷs medical history was not notable except for hypertension. Before visiting our outpatient clinic, the patient had undergone neurologic examinations at the neurologic department, including a brain MRI, which found no abnormal lesions in the central nervous system. The patientвҖҷs pain was restricted to the left facial area and recurred daily, lasting for several hours, and was aggravated when the patient touched their nose. A sinonasal endoscopic examination was performed by an experienced rhinologist, and a severe septal deviation to the left side was identified. The deviated portion appeared impacted on the medial mucosa of the left inferior turbinate suggesting a mucosal contact point (Fig. 1). The mucosal color of the impacted septal area was a little yellowish, differentiating it from the other parts of the septum. Paranasal (PNS) CT scans were performed to evaluate the abnormalities in the sinonasal cavity. A severely deviated bony septal abutting the medial part of the left inferior turbinate was identified in the left nasal cavity; there was no other inflammatory lesion in the sinonasal area (Fig. 2). The patient did not complain of rhinologic symptoms, such as rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, or somatosensory symptoms. A small 5% lidocaine and epinephrine-soaked cotton pledget was applied to the contact point, and the change in pain was assessed by the visual analog scale (VAS). We used a standardized 100-mm VAS ruler, and the patient was asked to indicate the severity of symptoms from 0 mm (no symptoms) to 100 mm (most troublesome). The VAS score for the left facial pain was reduced from 70 mm to 20 mm. We suspected that mechanical trauma to the deviated nasal septum induced the damage to the severely deviated septal mucosa and iatrogenically induced the associated headaches, and might also be the reason for the patientвҖҷs facial pain. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with persistent idiopathic facial pain, possibly originating from mechanical damage mucosal to the contact point caused by the nasopharyngeal swabbing. For treatment, surgical correction was considered; however, due to the patientвҖҷs age, a conservative management approach with analgesics, steroid nasal spray, and reassurance was used. Until 3 months follow up, the patient complained facial pain which was relieved by analgesics.

Discussion

A mucosal contact point refers to the contact of the nasal septal mucosa with the lateral nasal wall [6]. A mucosal contact headache is a secondary headache disorder described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders second edition (ICHD-2) [6]. However, mucosal contact headaches have been controversial due to limited evidence, and the ICHD third edition (ICHD-3) no longer includes them in their listed disorders [7,8].

In this patient, a neurologic deficit was excluded by a neurologist. We could not find any abnormalities in the sinonasal cavity related to the facial pain, except for the severe septal deviation and mucosal contact point between the nasal septum and inferior turbinate. Upon closer evaluation of the septal mucosa, we found that the mucosal color in the mucosa contact area was yellowish and discolored (Fig. 1, circled). Since the patient had no facial pain before the COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab, and the severe facial pain developed immediately after, we suspected that the pain was due to the injury on the mucosal contact point induced by a blinded nasopharyngeal swabbing. To diagnose the persistent facial pain due to nasopharyngeal swab, other possibilities such as neurologic or rhinologic diseases should be excluded such as in our case.

Although the patient already had a severe septal deviation before the nasopharyngeal swab, discovered by the bony deviation shown on the PNS CT, the blinded swabbing might have induced damage to the pre-existing mucosal contact point. The painвҖҷs origin was further supported when the symptoms were relieved by applying local anesthetics to the mucosal contact area. Therefore, we suggest that the headache, diagnosed as вҖңidiopathic facial pain without somatosensory changes,вҖқ was not directly caused by the mucosal contact point but could have been caused by mechanical damage to the underlying mucosal contact point.

Poor familiarity with common nasopharyngeal structural variations, such as septal deviations, could lead to unexpected complications [1,9]. Complications requiring surgical management, such as epistaxis, septal abscess formation, and CSF leakage, have been reported after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swabbing [4,5]. Nasopharyngeal swab induced pain and discomfort in the tested area also have been previously reported [10,11]. This case report describes another potential complication of nasopharyngeal swabbing, persistent idiopathic facial pain without somatosensory changes, related to a pre-existing mucosal contact point. To decrease the possibility of these potential complications, we suggest performing CottleвҖҷs maneuver when performing a nasopharyngeal swab or asking subjective questions about breathing and the preferred nostril before performing a nasopharyngeal swab [12]. Training to understand the anatomic variations and to recognize the possible complications of nasopharyngeal swabbing will be beneficial to minimize complications.