|

|

AbstractIatrogenic skull base injury may occur during sinus surgery, and endoscopic repair is considered the gold standard for treatment. We report a 65-year-old male who experienced an iatrogenic ethmoid roof defect caused by endoscopic sinus surgery, eventually leading to four reoperations of endoscopic repairs. Autologous fascia lata and contralateral nasoseptal flap were mainly utilized for this revision case. Following 29 days of hospitalization, which included absolute bed rest with lumbar drainage for 22 days, there was a gradual improvement in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profile and mental status. Additionally, the patient underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement to address non-obstructive hydrocephalus resulting from meningitis, ultimately allowing him to return to his normal daily life. Critical factors in managing large skull base defects with high-flow CSF leakage include multi-layer reconstruction with fascia lata and a pedicled nasoseptal flap, sufficient control of intracranial pressure with CSF drainage and positioning, and infection control through appropriate antibiotics.

IntroductionTraumatic skull base injuries could be occurred by iatrogenic injuries during operation. The most common cause of iatrogenic skull base injury is endoscopic sinus surgery [1]. The use of powered instrumentation along the skull base makes the iatrogenic case more dangerous [2]. Generally, the endoscopic surgery for any type of skull base defect is the gold standard. The multi-layered reconstruction with the combination of fascia lata and pedicled nasoseptal flaps provides reliable results [3]. Here, we describe a case with high-flow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage through the large iatrogenic skull base defect, managed by endoscopic approach.

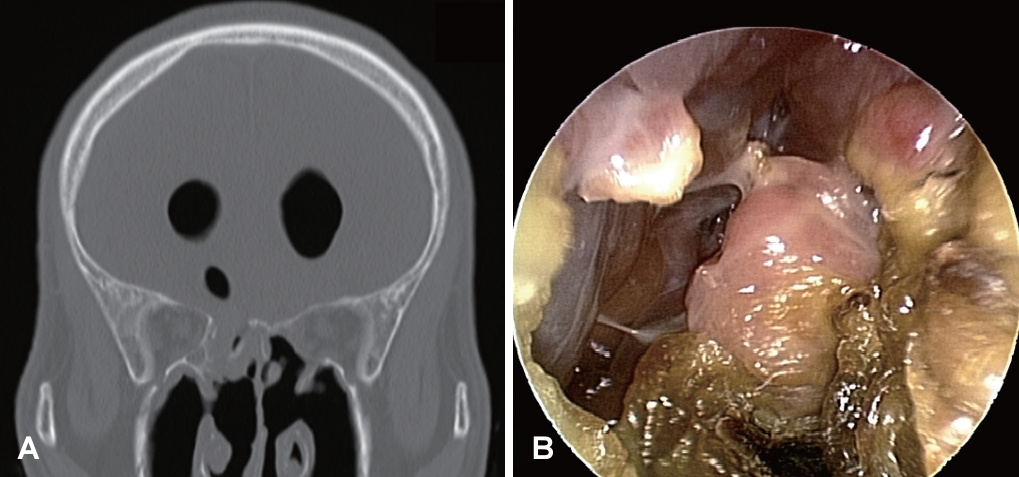

CaseA 65-year-old male patient presented with recurring CSF leakage. Formerly in good health, aside from asthma, initial CSF leakage occurred presumably after bilateral endoscopic sinus surgery and septoturbinoplasty at local hospital. Subsequently, due to an altered conscious status after sinus surgery, he was transferred to another tertiary hospital. Magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging revealed a skull base defect in right ethmoid roof defect, tension pneumocephalus, brain parenchymal damage, and bilateral lamina papyracea (LP) defect (Fig. 1).

At the previous hospital, endoscopic skull base repair was performed using an ipsilateral septal flap. Although pneumocephalus appeared to decrease immediately after surgery, CSF leakage recurred repeatedly despite of the second and third revision surgeries. Following the last surgery, follow-up CT scan showed the diffuse ventricular dilatation and a skull base defect at the right posterior ethmoid roof (Onodi cell) (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the patient transferred to our center for the reoperation. At the initial visit to our clinic, no overt CSF leakage was evident upon endoscopic examination (Fig. 2B). However, intermittent fever spiking up to 38.3°C and worsening drowsiness in the patient implied the meningitis.

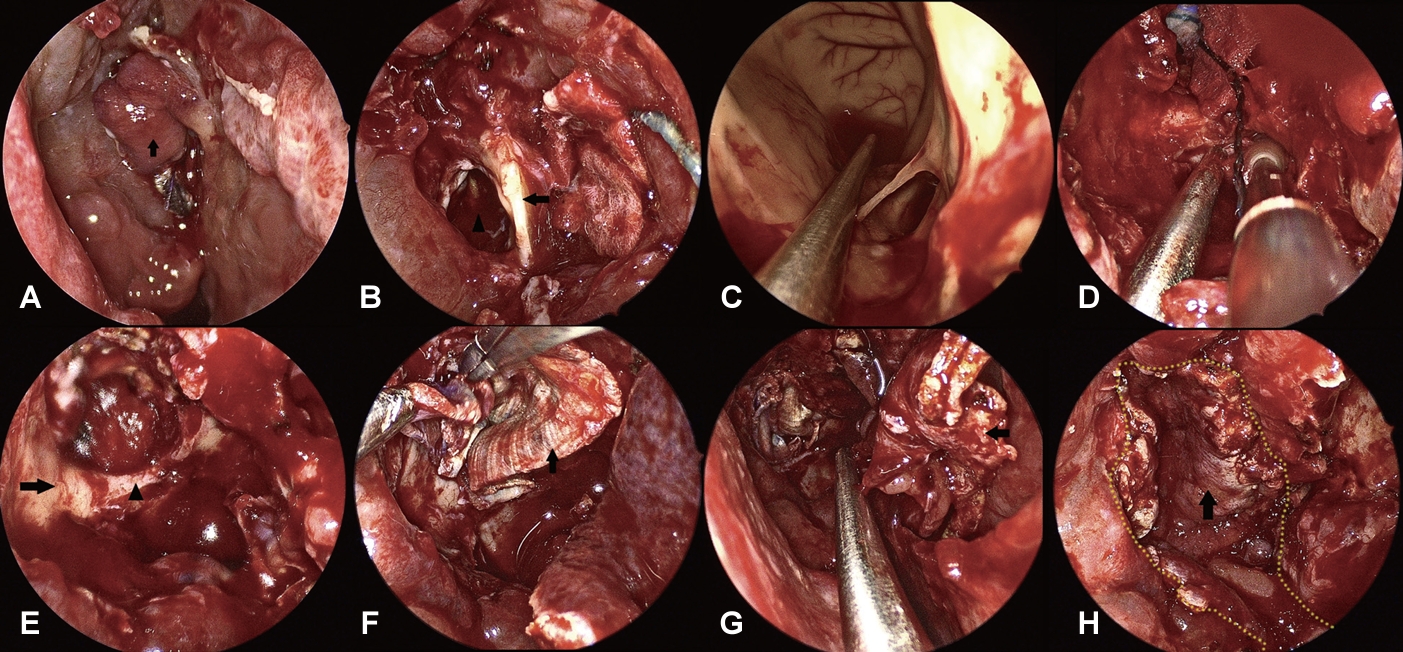

Skull base defect was partially covered with ipsilateral mucosal flap from the previous tertiary hospital under the intraoperative endoscopic view (Fig. 3A). Active CSF leakage was identified along the inferior border of Onodi cell. Septal cartilage graft and abdominal fat graft were covering the 10 mm-sized skull base defect after the meticulous dissection of the previous septal mucosal flap (Fig. 3B). After removal of compacted materials with the conception of the debridement, the frontal horn of right lateral ventricle was exposed through the cerebromalatic basal frontal lobe (Fig. 3C). With temporary gauze packing, inflamed mucosa of sphenoid sinus and Onodi cell border was peeled off and drilled to secure clear, smooth, and non-infected bone margin where the new pedicled nasoseptal flap could be engrafted (Fig. 3D). During these procedures, optic nerve canal was identified and saved (Fig. 3E). Skull base defect was reconstructed with the double-layered autologous fascia lata from right thigh in fashion of buttress (Fig. 3F). Contralateral nasoseptal flap extending to nasal floor was elevated to obtain the sufficient length and size to cover the skull base defect (Fig. 3G and H). Margin of nasoseptal flap was anchored with Surgicel (Ethicon, J&J Surgical Technologies, Arlington, TX, USA) followed by the applying DURASEAL (COVIDIEN, Waltham, MA, USA) and nasal cavity packing with absorbable materials.

Lumbar drain was preoperatively inserted in the operating room, with pressure level zeroed by bed height. Throughout the hospital course, to prevent flap dislodgement and CSF leakage, the patient was required to maintain absolute bed rest (ABR) without any head elevation. Vancomycin and 3rd-generation cephalosporin were admitted covering meningitis. Intraoperative tissue culture revealed methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, despite CSF culture results consistently revealing as negative.

Follow-up CT scan showed the no acute hemorrhage nor progression. However, the patient experienced delirium featured with visual hallucinations and disorganized speech/limb movements, necessitating management with antipsychotics such as haloperidol or quetiapine. The conscious status and orientation improved rapidly, allowing to taper off psychiatric medications. CSF profile showed gradual improvement, and fever subsided within 5 days (Fig. 4). After 22 days of maintaining ABR position, the lumbar drain was removed after confirming the well-engrafted viable pedicled mucosal flap and no evidence of CSF leakage (Fig. 5). However, the follow-up CT scan three days after removing lumbar drain showed the progression of ventriculometaly. After ventriculoperitoneal shunt, the patient was discharged, walking without any neurological sequelae.

DiscussionThis case exhibits distinct features compared to typical skull base defect cases. Firstly, it was large defect resulting from iatrogenic trauma, and subsequent infection. After the pedicled nasoseptal flap technique was introduced, failure rate decreased from 33% to 5.4% in large skull base defect repair (>20 mm) [4]. A recent study demonstrated that the endoscopic closure rate was 91% after primary surgery for large skull base defects and 98% in small (<11 mm) and midsized defects [3]. In cases of iatrogenic injury, loss of dura and gray matter due to the use of powered instruments makes the case more complicated [1]. The development of hydrocephalus following a large defect is even more uncommon and challenging [5]. The intraoperative findings of our case also showed an extensive defect with exposed ventricles, which made the repair surgery complex.

Secondly, it was a fourth reoperation case. No obvious CSF leakage was observed on our initial examination because the defect was already covered by fat and a previous septal graft. However, the presence of bacterial meningitis still indicates an invisible active leak [6]. Even in the absence of an obvious leak, surgical exploration is indicated if the patient presents with infectious or neurologic symptoms [7]. Successful reoperation with additional trimming and contralateral nasal septal flap is also indicated.

Lastly, the patient was maintained in the ABR position with lumbar drainage. In a meta-analysis of 1568 cases of CSF leaks, 761 lumbar drains were used for up to 10 days [8]. The use of lumbar drainage for more than 20 days in this case was due to a large, high-flow CSF leak with the defect reaching directly into the lateral ventricle, and central nervous system (CNS) infection. In addition, daily active surveillance in the CSF laboratory was required to accurately assess the patient’s recovery and control of meningitis, since dirty wound or CNS infection disturb the engraftment of reconstruction materials. Active caregiver attention and appropriate antipsychotic medication were critical because it was difficult to maintain ABR for long periods of time, especially in delirious patients [9].

In conclusion, iatrogenic skull base defect caused by powered instruments can be successfully treated with endoscopic surgery using a combination of pedicled nasoseptal flap and autologous fascia lata. In addition, for large iatrogenic defects with infectious condition, long-term hospital management and supportive care with postoperative lumbar drainage could be considered.

NotesAuthor Contribution Conceptualization: Doo Hee Han. Data curation: Doo Hee Han, Hae Chan Park. Formal analysis: Hae Chan Park. Investigation: Hae Chan Park. Methodology: Doo Hee Han. Project administration: Doo Hee Han, Yong Hwy Kim. Supervision: Doo Hee Han. Validation: Yong Hwy Kim. Visualization: Hae Chan Park. Writing— original draft: Hae Chan Park. Writing—review & editing: Doo Hee Han, Yong Hwy Kim. Fig. 1.Initial (post-traumatic) images. A: T1-weighted MRI revealing a defect connected to the ventricles. B: CT findings indicating a right ethmoid roof defect and tension pneumocephalus. C: Left lamina papyracea defect.

Fig. 2.Preoperative CT and 0º endoscopic findings. A: Slightly decreased, but still notable amount of pneumoventricle and pneumocephalus compared to initial post traumatic findings. B: Endoscopic examination showed no definite evidence of overt cerebrospinal fluid leakage.

Fig. 3.Intraoperative endoscopic views (0º endoscope). A: Previous mucosal flap (arrow). B: Previous septal cartilage graft (arrow). 10 mm skull base defect on the left (arrowhead). C: Lumen of lateral ventricle. D: Gauze packing at the defect opening and onodi cell border being drilled. E: Drilled margin of skull base defect (arrow) and optic nerve canal (arrowhead). F: Autologous fascia lata (arrow). G and H: Contralateral nasoseptal flap (arrow). Yellow dots stand for contour of the flap margin.

REFERENCES1. Church CA, Chiu AG, Vaughan WC. Endoscopic repair of large skull base defects after powered sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129(3):204-9.

2. Kubik M, Lee S, Snyderman C, Wang E. Neurologic sequelae associated with delayed identification of iatrogenic skull base injury during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). Rhinology 2017;55(1):53-8.

3. Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Rioja E, Enseñat J, Enriquez K, Viscovich L, Agredo-Lemos FE, et al. Management of anterior skull base defect depending on its size and location. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:346873.

4. Kassam AB, Thomas A, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Vescan A, Prevedello D, et al. Endoscopic reconstruction of the cranial base using a pedicled nasoseptal flap. Neurosurgery 2008;63(1):ONS44-53.

5. Salih HR, Jaafer H, Ismail M, Khallaf AK, Mohammed AJ, Al-Mosawy MSMJ, et al. Extensive tension pneumocephalus presented in the setting of a challenging etiology. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:570.

6. Gray ST, Wu AW. Pathophysiology of iatrogenic and traumatic skull base injury. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 2013;74:12-23.

7. Miller JD, Taylor RJ, Ambrose EC, Laux JP, Ebert CS, Zanation AM. Complications of open approaches to the skull base in the endoscopic era. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2017;78(1):11-7.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|