Introduction

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) is a condition in which hearing loss ≥30 dB occurs at three or more consecutive frequencies within 3 days [1]. It is accompanied by vertigo in about 30% of cases, and in clinical settings [2], it is defined as SSNHL with vertigo or labyrinthitis [3,4]. However, if direction-changing spontaneous nystagmus or direction-changing gaze-evoked nystagmus is observed, additional evaluations should be performed to differentiate central causes such as anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) infarction and vestibular schwannoma. However, congenital nystagmus appears as involuntary, periodic eye movements starting 3 months after birth when gaze stabilization ability begins to develop, accompanied by a decrease in gaze stabilization ability [5]. It may be recognized by the family in the early postnatal period or may not be noticed until adulthood when there is an eye disease or neurological disorder, and the presence of nystagmus is recognized through eye movement tests. If a patient is unaware of the presence of congenital nystagmus, the diagnosis may become extremely challenging when accompanied by acute peripheral nystagmus. Herein, we report a case of SSNHL with vertigo in a patient with previously undiagnosed congenital nystagmus, along with a literature review.

Case

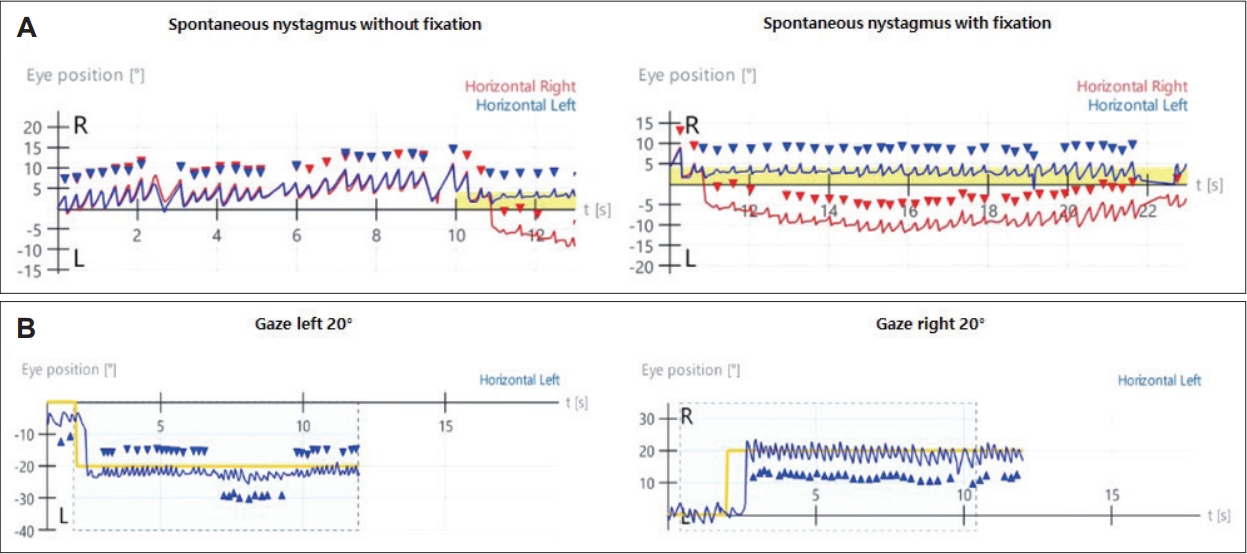

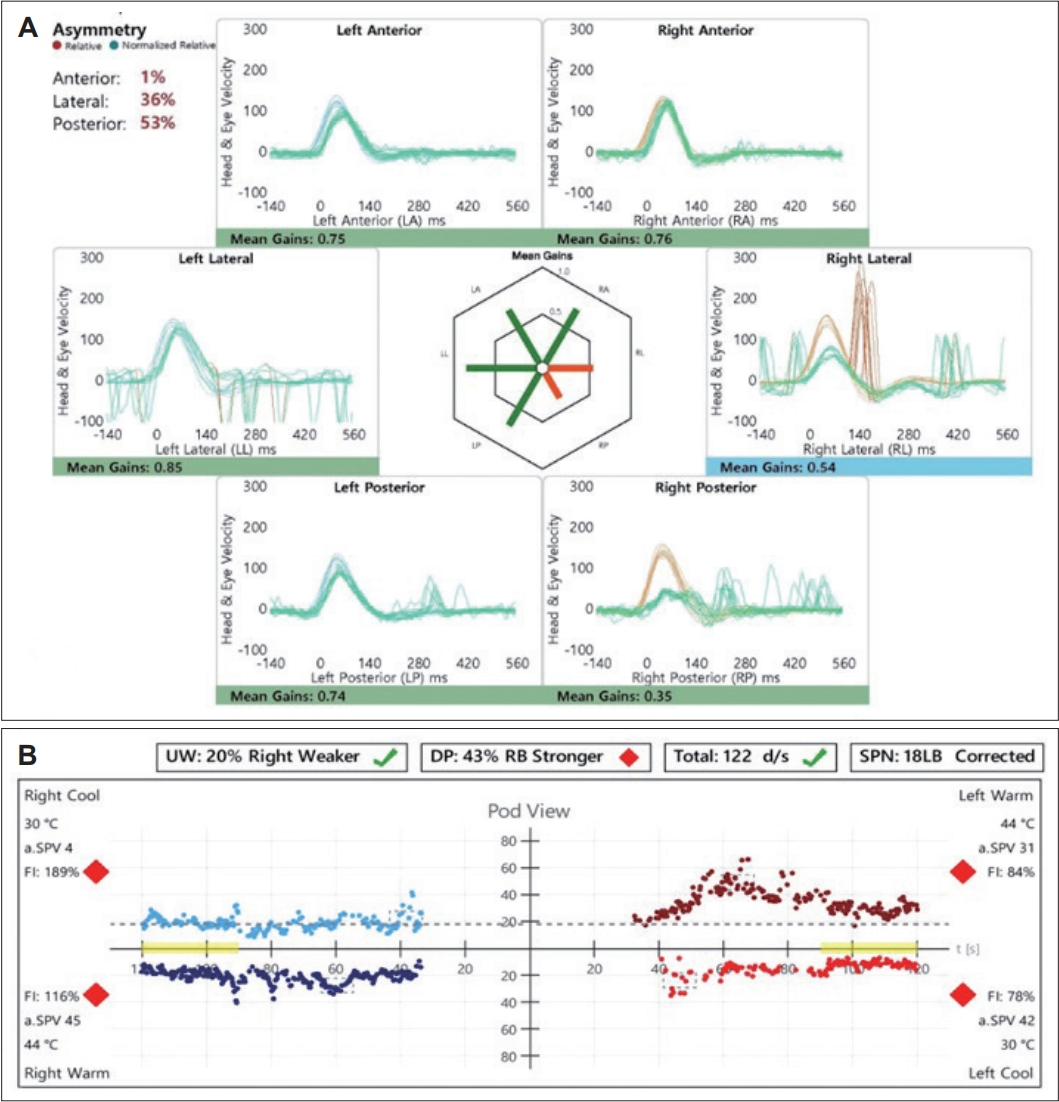

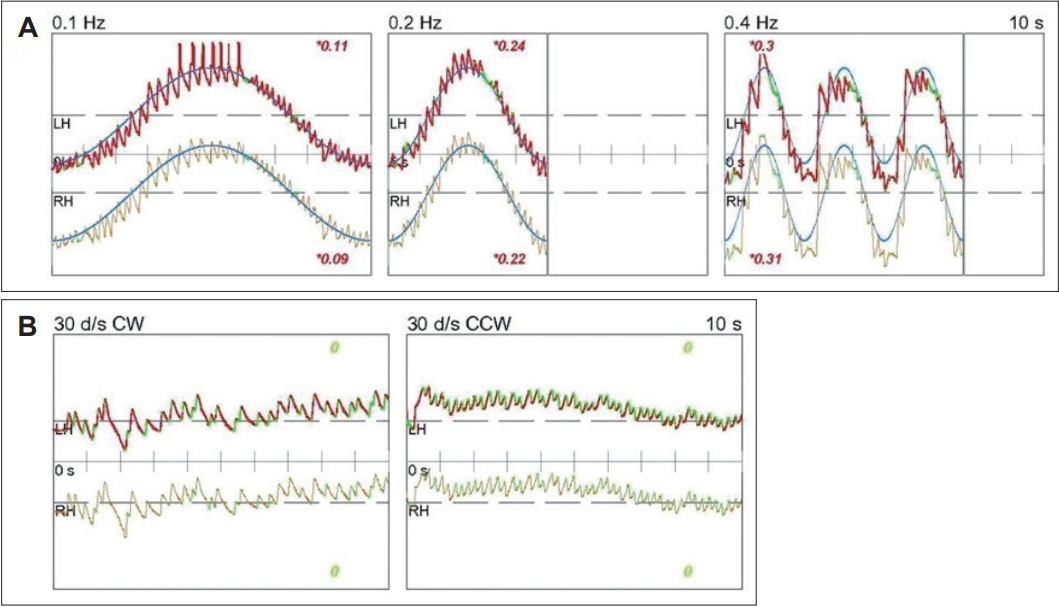

A 33-year-old female with no significant medical history presented with dizziness and right-sided hearing loss that began 6 days prior to her visit. The patient was admitted to another hospital 6 days prior and was diagnosed with right-sided SSNHL and treated with high-dose steroids. No abnormal findings were found on the brain MRI performed to differentiate the central causes. However, due to persistent dizziness after discharge, the patient was admitted to the otolaryngology department through the emergency room of our hospital to continue high-dose steroid treatment (methylprednisolone 48 mg/day for 7 days, followed by a tapering of 8 mg each day) and to conduct further tests for dizziness. The tympanic membranes were normal, and pure tone audiometry (6-division method) revealed severe hearing loss with an air conduction (AC) threshold of 91 dB, and bone conduction (BC) threshold was scaled out on the right side. On the left side, the AC and BC thresholds were both 8 dB. Repeated videonystagmography showed left-beating spontaneous nystagmus (17 d/s) without fixation, periods of foveation with fixation, and direction-changing gaze-evoked nystagmus (Fig. 1, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Left-beating nystagmus was observed in both the Dix-Hallpike and Bow and Lean tests, whereas geotropic nystagmus was observed on the right (12 d/s) and left (46 d/s) during the head-roll test. The video head impulse test showed decreased gain and catch-up saccades in the right lateral semicircular canal (0.54) and posterior semicircular canal (0.38); 20% right lateral semicircular canal paresis was confirmed in the caloric test (Fig. 2). Although peripheral lesions in the right vestibulocochlear system were evident on pure-tone audiometry and vestibular function tests, central causes were suspected based on a gaze stabilization index ≥70% from the caloric test and direction-changing gaze-evoked nystagmus. No abnormal findings were observed on brain diffusion-weighted MRI performed on the seventh day after onset to differentiate delayed AICA infarction. On the following day, decreased gain, asymmetry, phase lead, and reduced time constant on the rotary chair test were observed, consistent with the findings of right vestibulopathy. However, a bidirectional sawtooth pattern in the smooth pursuit test and bilateral reversed optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) were observed on 30 d/s of the OKN test (Fig. 3). A meticulous re-examination of the medical history was conducted in light of the potential existence of undiagnosed congenital nystagmus, which the patient may not have recognized because of the absence of discomfort. At an ophthalmology clinic that the patient had visited before being diagnosed with SSNHL, she had been informed that she had eye tremors; however, she did not receive a specific diagnosis. Furthermore, upon consultation with her family, a history of noticeable eye tremors while attempting to focus on someone nearby was confirmed. Based on the patient’s medical history and the results of the smooth pursuit and OKN tests, the patient was diagnosed with pre-existing congenital nystagmus but did not experience significant discomfort due to the nystagmus null point located in the center. Spontaneous left-beating nystagmus occurred due to right labyrinthitis, and gaze-evoked nystagmus occurred due to preexisting congenital nystagmus. The patient was treated with medication for dizziness and the steroid dosage for 5 days. On the 16th day of the treatment, the patient was discharged and reported no discomfort in daily life. As the patient did not visit the outpatient clinic, further follow-ups were not performed.

Discussion

SSNHL occurs abruptly without any specific cause and is presumed to be caused by viral infections or circulatory disorders. In severe cases, dysfunction may occur in both the cochlear and vestibular systems, leading to vertigo in 30%-40% of cases [2,6]. On the other hand, SSNHL accompanied by vertigo can occur due to lesions in the central nervous system, with AICA infarction and acoustic neuromas as major causes. In more than 90% of the cases, the labyrinthine artery originates from the AICA, and AICA infarction causes ischemic damage to the inner ear, leading to acute vertigo and hearing loss [7]. Tumors of the cerebellopontine angle can also cause SSNHL, with vestibular schwannomas having the highest incidence. Therefore, it is important to differentiate posterior fossa lesions before treating patients with SSNHL accompanied by vertigo, and MRI is known to be the most effective diagnostic method [8].

Periodic alternating and direction changing nystagmus have been reported in peripheral vestibular disorders [9]. However, previously reported cases changed to unilateral spontaneous nystagmus within 2 days [9]. Because of its peripheral origin, the nystagmus was suppressed by visual fixation, and both smooth pursuit and OKN tests were normal [9]. In contrast, bidirectional saccadic pursuit and reversed OKN were observed in our case, leading to the consideration of central lesions. Whether this was acquired or congenital was determined by additional MRI, and patient and family statements. No acute central lesion was found in the initial MRI which was performed a week after the onset, and the patient was diagnosed with congenital nystagmus after hearing the statement that there were eye tremors when looking sideways since childhood.

Congenital nystagmus is an involuntary, periodic eye movement that occurs from three months of age and is classified into three types depending on the pattern: jerk, pendular, and combined [5,10]. Although hereditary cases have been reported, the cause remains unclear. In some instances, nystagmus is believed to result from the erroneous formation of neural pathways involving abnormal crossing [11]. In most cases, MRI is performed as the first test; however, structural abnormalities are rarely found [12]. Huang, et al. [13] analyzed the presence of inner ear diseases in 50 patients with congenital nystagmus and confirmed that 17 patients had accompanying inner ear diseases, such as labyrinthine dysfunction, endolymphatic hydrops, sequelae of otitis media, and congenital hearing loss. Hence, interpreting nystagmus arising from labyrinthine disease can be challenging in patients with congenital nystagmus.

As defined by Kestenbaum [14] in 1948, OKN is an eye movement in which the eyes slowly track an object outside a train and quickly return to their previous direction once the object passes. In normal individuals, OKN shows slow eye movement in the direction of the stimulus, followed by fast eye movement in the opposite direction. However, in reversed OKN, slow eye movement appears in the opposite direction of the stimulus, followed by fast eye movement in the ipsilateral direction [15]. Such reversed OKN mainly appears in patients with congenital nystagmus and can be accompanied by cerebellar or brainstem abnormalities acquired later [13]. However, bidirectional reversed OKN appears only in congenital nystagmus [15].

There was no mention of abnormal eye tremors in the patient’s initial medical history. The patient and family did not recognize it as a pathological symptom, as it did not cause much discomfort in daily life. If patients experience no difficulties in their daily lives, they may live into adulthood without awareness of the existence of congenital nystagmus. Halmagyi, et al. [15] reported reversed OKN in 31 patients with congenital nystagmus. Among them, 29 were not diagnosed with congenital nystagmus until adulthood, as it remained unrecognized until incidental neurological symptoms developed, as in our case. In such cases, although making a diagnosis may pose a challenge, smooth pursuit and OKN tests could provide useful insights.

In conclusion, for patients with SSNHL accompanied by vertigo and direction-changing gaze-evoked nystagmus, prioritizing brain MRI to differentiate AICA infarctions is crucial. However, if no abnormalities are found on the MRI, vestibular function, smooth pursuit, or OKN tests should be performed. If bidirectional saccadic pursuit and reversed OKN are observed, a detailed medical history focusing on congenital nystagmus should be revisited with a strong suspicion of undiagnosed congenital nystagmus.